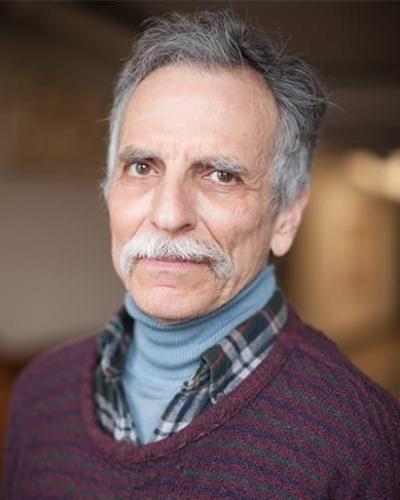

Professor Harold Hodes of the Sage School of Philosophy is sometimes reminded of an anecdote: At a reception for the 1994 Kyoto Prizes, two honorees, the French mathematician André Weil and the Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa, briefly discussed their achievements. “I have a great advantage over you,” Weil said to Kurosawa, “I can love and admire your work, but you cannot love and admire my work.”[1]

This line resonates with Hodes, who is very well aware that most people will never understand his academic output. “I think it’s great to have someone like Socrates teaching on the streets, but that’s not my thing,” says Hodes, “Just because the average person can’t understand something doesn’t mean it’s not worthwhile to do it.” Hodes works primarily in logic and the philosophy of mathematics, so he is accustomed to getting confused looks when he explains his projects. “I am interested in defending some version of logicism, the idea that an awful lot of mathematics is really fancy logic, which is to say higher order logic,” Hodes explains, “But I’m not sure how intelligible this is likely to be to someone without any philosophical training. I mean, what I do is kind of arcane.”

Hodes’s interests in the arcane date back to his childhood. “My father went to grad school in philosophy, though he never finished his PhD dissertation,” says Hodes, “He told me that he felt the greatest mistake he had made in his life was going to graduate school in philosophy rather than math.” Hodes’s father had a profound influence on his intellectual development. “I grew up surrounded by philosophy books and math books,” Hodes remembers, “When I began taking geometry, my father told me about Gödel’s theorem, and it was very interesting to me. My father died when I was 15, before I went to college, but of course, I followed exactly his path.”

Despite studying both philosophy and mathematics during his time as an undergraduate at Columbia, Hodes recalls that by his senior year, he was “whole-hog into philosophy.” Hodes continued his philosophical education as a graduate student at Harvard, during which time he found himself rubbing shoulders with some of the most acclaimed philosophers of the day. Among them was Willard Van Orman Quine, whose work Hodes had admired since high school. “When I got to Harvard, there were three people who believed everything Quine had said, namely Quine, Burt Dreben, and me,” says Hodes, “I was a TA for Quine. He was very remote. He’d give his introductory logic course, the same one every year, lecturing from these yellowed index cards which he had probably written up in the 40’s and was still using.”

Hodes would go on to write his dissertation under the supervision of another luminary, Hilary Putnam. “Hilary was a very hands-off advisor,” says Hodes, “He would say, ‘Read this paper… and come back with a dissertation!’ Meeting with Hilary consisted of my saying to him, ‘What are you working on?’ Then we’d have a really interesting long conversation about what he was thinking about.” Among Hodes’s other teachers at the time were Robert Nozick and Nelson Goodman; “Although I thought his politics were bad, I really did like Robert Nozick. You know, he was such a nice guy and really friendly and accessible and smart,” Hodes remembers. Meanwhile, he describes Goodman as having been “very severe. He kind of seemed like a Prussian general.”

After earning his PhD, Hodes joined the Sage School in 1977. It was around this time when Hodes began publishing some of his most influential work on modal logic, in which he investigates the limits of what quantifiers can express in modal languages. “I guess I was struck by the fact that there’s something schizophrenic about the standard model theory for quantified modal logic,” Hodes explains, “Bound variables are world-restricted; that is, relative to a world you want bound, variables range over the individuals that exist in that world. But free variables are supposed to range over all possible individuals.” This struck Hodes as a problem. “For example, it seems that it would have been possible that I had a brother, although I don’t actually have a brother. So do we want to say that there is a non-actual brother that I have? No, we wouldn’t want to say that. At least Quine would make fun of you if you did. I was disinclined to believe that there are non-actual possible entities. So, that naturally led to the question of how you express the thought that there could have been something that doesn’t actually exist. And in standard model first-order modal language, you can’t express it.”

Although Hodes says he feels like he’s “still in the modal logic game,” his more recent work has had a different focus. In addition to his writings on logicism, Hodes has been devoting much of his attention to logical syntax and a longstanding interest in non-bivalent logics (that is to say, logics in which there are truth values besides “true” and “false”). Much of this work is interdisciplinary. “I’m on the interface between philosophy and mathematics,” says Hodes, “I like to find topics that have philosophical motivations but can be addressed with mathematical means. These boundaries are only relevant to the registrar’s office.”

Though his work may seem dense to some, making philosophy accessible has been a core aspect of Hodes’s teaching career. Hodes is the Sage School’s director of undergraduate studies, and often teaches undergraduate logic courses and seminars on the history of 20th Century philosophy. And, of course, the philosophy-themed cartoons that decorate his office door are well-known to the student body. His favorite of these is a three-panel Calvin & Hobbes making light of the malleability of language.[2] It seems there is room for fun even in the arcane.