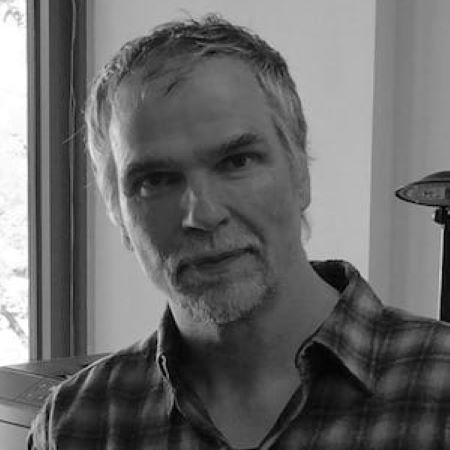

When Dr. Justin Steinberg was in high school, he remembers going into a bookstore and seeing “a whole shelf devoted to this guy whose name I couldn't pronounce.” The author in question was Friedrich Nietzsche, one of whose books Steinberg bought and read on a whim. “It completely floored me,” he recalls, “That was my first exposure to philosophy, and I was like, this is amazing.” Growing up in a small town in central Michigan, Steinberg describes discovering philosophy and literature as a personal and intellectual revelation. “I just wasn't aware that people that lived well before me had similar thoughts to the thoughts that I was having, or were questioning society in the ways I was,” he says, “but then I discovered all these ways in which norms and questions of value were being interrogated in a way that was pretty thrilling to me.”

Still, becoming a philosopher wasn’t a certainty for Steinberg. After graduating from college, he took a job in social work, and considered pursuing it as a career. But he found himself “itching for intellectual stimulation.” He recalls reading Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics during lunch breaks, or coming home after a grueling day of work eager to discuss Daniel Dennett with friends. It was during this time that Steinberg began taking the idea of doing philosophy seriously. “I was realizing something about myself,” he explains, “which is that my flourishing really depended on being able to continue to pursue philosophy. And I didn't have an end goal in mind. I just knew I wanted to do more of it.”

Going into graduate school, Steinberg remembers having various ideas about what areas he wanted to specialize in. Philosophy of language, philosophy of mind, and phenomenology were all leading candidates. So it came as a surprise, he says, when “I wound up working on the history of 17th-18th century philosophy and particularly on Spinoza, which was the furthest thing from what I expected I would do.” Steinberg discovered Spinoza during a first-semester seminar on continental rationalism, and it left a lasting impression on him. He was particularly struck by Spinoza’s attempt to give an account of action and freedom that was consistent with naturalism. “It actually felt like I was pursuing historically some of the things that Dennett was getting me to think about in contemporary philosophy,” Steinberg says, “How to be a naturalist and how to be free.”

Steinberg’s interest in Spinoza’s conception of action and freedom would lead him to publish Spinoza’s Political Psychology: The Taming of Fortune and Fear, a book which explores how Spinoza thought the state could effectively facilitate human freedom. Writing the book wound up being more difficult than Steinberg expected (“I guess I didn't appreciate the extent to which telling a story in which all of the parts kind of hang together is itself a real challenge”). But it ultimately proved rewarding. “There's something about the satisfaction that comes from feeling like you've crafted a narrative that if one were to pick up at the start,” he explains, “then hopefully by the time they get to the end, they see that there's this integral organic unity to the whole piece.”

Currently, Steinberg is branching out to other areas of early modern philosophy. He has ongoing projects on Thomas Hobbes, Émilie du Châtelet, as well as some early radical figures in 17th century England. In addition, he’s working on how early modern philosophers thought about individuation and social ontology, paying attention to their views on the construction of social life. But Spinoza is still near and dear to his heart. He has in mind a future project defending Spinoza’s conception of belief formation, desire, affects and emotions. Spinoza’s original account, he thinks, might be preferable in certain ways to many contemporary accounts, including Spinoza inspired ones.

Such a project, Steinberg admits, will require a fair amount of work. But the thought of engaging with contemporary literature on moral psychology excites him. “I got into doing history of philosophy not because I'm simply interested in historical curiosities,” Steinberg says, “but because I wanted to pursue the philosophical questions alongside historical thinkers.” Furthermore, the prospect of showing that Spinoza’s views are worth taking seriously today is important to Steinberg. “I think that in some ways, those of us that work in history are discouraged or have learned to suppress a natural question after we've tried to interpret something in the best possible light, which is just, is there anything to this?” he explains, “And I think maybe we should take that next step and take that question seriously.”

For Steinberg, the relevance of history extends beyond academia. He is heartened by the increasing number of philosophers engaging in public philosophy, especially in relation to contemporary issues like social media and AI. But he thinks there’s room for history to play a role as well. “In some ways, I would like to do some forms of public philosophy that just get us away from all of that. Get us to think in a totally different way and almost try to inhabit a totally different world,” Steinberg says, “I think that can be valuable. And there's a hunger for that as well.” He receives enthusiastic reception when speaking to non-professional audiences about Spinoza. “You would get retired physicians and people that had all sorts of life experiences,” he says, “and you could see them just light up as you're talking through these historical theories.”

This transformative power of philosophy is something that Steinberg has experienced personally. Reflecting on the dissatisfaction with his environment that led him into philosophy, Steinberg credits working on Spinoza with giving him a better appreciation for the reasons why people have the values and beliefs that they do. He hopes that “the more we can get behind just the expression of values to understand the source of values, then the more we can come to understand one another and have intelligible, productive conversations.”

Having taught for many years in New York City, Steinberg is looking forward to indulging his love for the outdoors in Ithaca, where he has already mapped out every hiking trail in the area. He is excited to be a part of the Sage School of Philosophy, where he will be able to work and teach with his spouse.