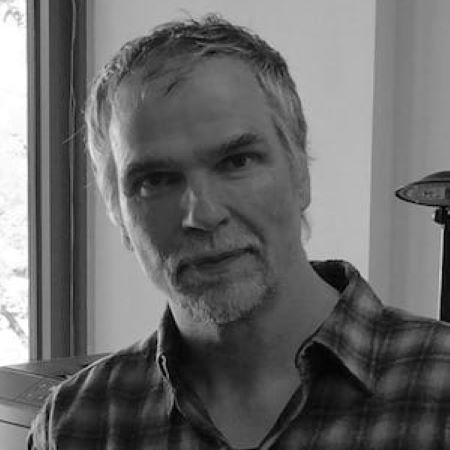

Professor Emad Atiq had broad disciplinary interests before he became interested in philosophy. His undergraduate studies initially focused on economics and mathematics. “I formed the idea early on of pursuing graduate study, following the example of my grandfathers,” he said, “I wanted to pick a subject and study it rigorously, but had difficulty choosing between several attractive options.” As a sophomore, he stumbled into a class on metaphysics and epistemology taught by Gideon Rosen, who would later become one of his PhD advisers. “Here's a course that made me think, gosh, I really need to rethink my starting points,” Atiq said, “What you are, why you exist, what role you serve… you think you have the basics figured out. Then you discover that you don’t.”

The initial encounter with philosophy was unsettling. “It made me realize I was an overly self-assured undergrad,” he said, “confused in ways I hadn’t appreciated until that point in my life.” At the same time, Atiq learned to find joy in rebuilding his convictions and described the process as invigorating: “I’m quite romantic about this sort of thing. I experienced a reverence for reality in all its complexity.” Atiq never lost his interest in other disciplines, but continued on in academic philosophy because of the unique intellectual rewards: “I’m interested in many things, but there was something about philosophical reflection that had an extra payoff I wasn’t getting elsewhere.”

An MPhil. at the University of Cambridge was an opportunity to explore the subject further. Atiq credits his supervisor at the time, Simon Blackburn, for strengthening his resolve to return to Princeton, his undergraduate alma mater, for a PhD. Atiq was also jointly pursuing a JD at Yale Law School and reflects on this period fondly. “I thoroughly enjoyed graduate school. I had a wonderful committee consisting of brilliant and nurturing philosophers: Gideon Rosen, Michael Smith, Sarah McGrath, and Philip Pettit. I would often show up to their office unannounced, and they would welcome me in, and we'd have lovely conversations.” Atiq still remembers many of those exchanges, which were “so stimulating, so intense and open-minded,” and recalls his conversations with his friends and peers just as fondly. “Your peers are often a source of philosophical wisdom and encouragement,” Atiq said. In addition, he found inspiration in the philosophers whose work he studied most closely, such as David Hume, Immanuel Kant, Bertrand Russell, and Ronald Dworkin.

When it comes to Atiq’s current research, he has two main areas of study – one in ethics and epistemology, the other in legal philosophy. Atiq described his general research project as motivated by an interest in how norms and normativity fit into our general picture of reality. “I'm interested in understanding norms. There are moral norms that tell us how to conduct ourselves in relation to others, there are epistemic norms for how we should orient our beliefs in relation to the world [...] and then there are legal norms that tell us, for example, that no one should be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law.” However, Atiq also cautions against reading too far into the connections between his various interests. “In describing those individual projects,” he said, “you need to deal with each project on its own terms.”

In ethics, Atiq defends the claim that moral norms can be reasoned about objectively. He is interested in the puzzle of the amoralist. “We think that people have reasons to comply with important moral norms. For instance, if you can help someone in desperate need at minimal personal cost, you should,” Atiq explained, “but then you quickly run into the difficulty of people who don’t seem to care, who don’t seem to be moved to comply.” It is tempting to think that such agents are mistaken, and then the question becomes: what are they missing? Much of Atiq’s work in ethics develops an answer to this question, an answer based on his work in epistemology.

His epistemology focuses on the kind of knowledge that cannot be reduced to an awareness of facts: direct perceptual knowledge. “It’s the kind of knowledge you gain when you listen to a piece of music that you never heard before,” Atiq said, “you’re aware of the music with all its richness and the knowledge you gain then sustains and underwrites all kinds of complex inferences and judgments [...] but that initial encounter, the hearing, on my view grounds or underwrites a form of knowledge that is non-factual. It’s a very intimate direct awareness of the thing.” Atiq considers this type of knowledge to be under-examined, especially in ethics. He thinks it offers a solution to the puzzle of the amoralist. What amoralists lack is direct experiential knowledge of other people’s minds. Moral agents with ordinary levels of empathy do not have direct access to the mental lives of others, Atiq clarified, but empathy allows for an approximation of this type of knowledge. He said, “I see myself as trying to vindicate a very old idea that finds expression in a broad range of not just philosophical works but literary as well as religious works, and the thought is that we’re radically cut off from other people’s inner mental life, and maybe our insufficient concern for others can be explained in terms of this solipsistic delusion.”

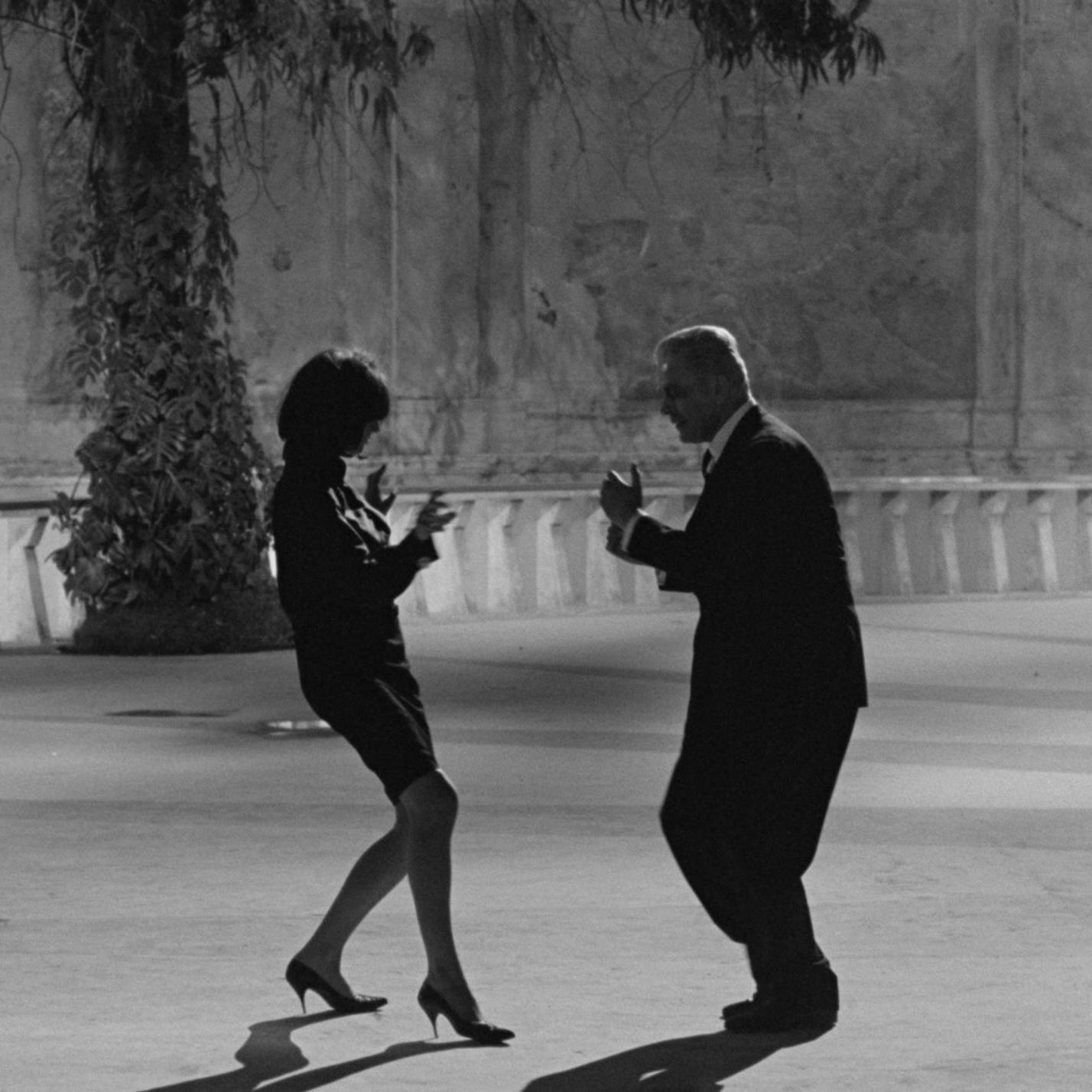

In legal philosophy, Professor Atiq has a short book coming out in a Cambridge University Press series on the philosophy of law. The book focuses on the relationship between legal reasoning and moral reasoning. He summarized, “The main thrust of the book is you can't understand law, legal norms, legal systems without understanding morality, without understanding what we're up to when we moralize, and without understanding our moral ideals.” Atiq points out that law is not reducible to morality. However, legal systems everywhere are made up of rules that are produced and promulgated with moral intentions. Ideals that we use to evaluate laws and legal systems, like reciprocity, interpersonal justice, and procedural fairness, are fundamentally moral ideals. “The law is a tool for realizing, promoting, or fostering a kind of fairness between persons,” Atiq said. He also maintains, building upon the views of Ronald Dworkin, that once you see law as this kind of tool, it becomes apparent that there’s a similarity between law and other artifacts that attempt to give form to an ideal—such as art. Specifically, Atiq argued “The language of the law is in many ways like the language we use to describe art.” In this vein, the work of the legal theorist and the work of the literary critic are similar. For example, even though critics have been debating the meaning of Hamlet for centuries, and despite the fact that art has a subjective element, the debate about what Hamlet means is not pointless. There’s room for disagreement, but the answer is not completely arbitrary or subjective. Even though Atiq doesn’t believe the comparison is quite as perfect as Dworkin originally imagined it to be, he thinks there are important similarities between the correct interpretation of a piece of art and the correct interpretation of law.

When Atiq is not working on his scholarly projects, he enjoys spending time with his wife and two daughters. “Before I had my kids, I did not know how much I’d enjoy being a father,” Atiq said, “They are a delight, and I learn from them every day.” Atiq’s wife is a soprano and works as a professor of voice at Ithaca College, so music plays a big role in their shared household. Their family often attends performances around Ithaca, which, Atiq pointed out, is “a very good town for music.” Atiq’s tastes are wide-ranging, and he enjoys everything from classical and jazz to folk rock, musical theater, and Pakistani music. In terms of hobbies outside of music, he enjoys rooting for the basketball team the New York Knicks, watches TV shows like The Wire and In Treatment, and though he doesn’t watch many movies, considers himself a big fan of Wes Anderson films. Lately, he’s been watching a lot of stand-up comedy.

When asked about his favorite saying, Atiq responded “I’ll have to think about it. For now, I’m afraid I can only offer you a joke about jokes that currently speaks to me: ‘When does a joke become a dad joke? When it becomes apparent.’”